Prison Reintegration

Preparing prisoners for successful re-entry into society.

|

How We Work

Our problem solving process is rooted in five key principles:

Focus on the outliers - those people or neighborhoods most likely to fall through the cracks of existing social welfare programs- to build better solutions for everyone. Set measurable, public, time-bound goals to build a sense of urgency and force key players to innovate. Engage the user - those trapped in poverty, along with frontline health and human services workers- to design more practical, better informed solutions. Optimize existing resources by using all available data to inform decisions about spending and community responses to need. Test and evaluate new ideas in short cycles to learn what works quickly and build on successful strategies. |

|

|

Social Reintegration

1. Start early

Until recently, the focus of organizations and government agencies has been predominantly on release programs, while ignoring the significance of pre-release programs. But as the Federal Bureau of Prisons philosophy states, "release preparation begins the first day of incarceration, [and] focus on release preparation intensifies at least 18 months prior to release." As you’ll see, successful reentry programs for inmates rely on more than just helping ex-offenders find jobs; it also requires helping offenders change their attitudes and beliefs about crime, addressing mental health issues, providing mentoring, offering educational opportunities and job training, and connecting them with community resources. Most, if not all, of these things can and should begin long before a person’s release date. 2. Clients, not offenders When government agencies and social service organizations just see "offenders", they often serve up a one-size fits all approach that ends up fitting no one. However, in a comprehensive report released by the Council for State Governments Justice Center, Integrated Reentry and Employment Strategies, they make a strong case that employment programs need to move beyond traditional services. Instead, they recommend addressing individuals’ underlying attitudes about crime and work, making them more likely to succeed at getting and keeping jobs and less likely to reoffend. Not all offenders share the same risk levels or needs, and learning how to accurately assess these attributes and deliver customized help is an important element to truly helping people get out of the criminal justice system. Programs like Operation New Hope’s Ready4Work, which has been recognized by 3 successive presidents, succeed by recognizing these people as people and individuals first and by creating programs that address their diverse needs. 3. Reassess frameworks According to MDRC, an organization committed to learning what works to help improve the lives of low-income people, "There is a growing consensus that reentry strategies should build on a framework known as Risk-Needs-Responsivity (RNR)." The framework helps organizations assess individuals’ risk levels for recidivism and provide appropriate levels of response. Along the same lines, models like Hawaii’s Opportunity for Probation with Enforcement (HOPE) aim to change how we look at probation and post-incarceration monitoring. Since more than half of recidivism is a result of technical violations of parole, this is an important part of the reentry process to examine. By trying new methods, tracking efforts and outcomes, and holding organizations accountable, we can move towards a system of reentry programs for inmates that serve their function while minimizing negative side effects. 4. An insistence on evidence I’m sure you knew it was coming, but it may surprise you to learn that previously there was very little evidence available to help determine what makes prisoner reintegration programs successful. Most organizations and government agencies were flying blind. To quote our white paper, It Takes A Village, "given the significant dollars issued in every state to community-based partners to execute specialty services for vulnerable populations, the limited view and engagement model represents a massive barrier to genuine collective practice and progress monitoring. Information systems are silo-ed, agencies have ‘policies’, and service providers often have multiple hands that feed them." However, with the advent of tracking tools like Social Solutions’ Efforts to Outcomes (ETO) software, government agencies can now insist on increased reporting and improved outcomes from their programs and community partners. By taking an evidence-based approach now, we can save states millions of dollars or more in the long run and truly help both John and Tom get back on their feet again. |

Criminal Justice Re-entry

People who are released from jails and prisons are among those most vulnerable to homelessness. These individuals often have few resources and may not have a support system in the community to which they are returning, particularly after lengthy periods of incarceration in prisons. The criminal records that follow formerly incarcerated people, even after they have served their sentences, can be obstacles to finding housing and employment. Many former prisoners have a substance abuse disorder, mental illness, or co-occurring challenge that may have gone untreated while they were incarcerated. All of these factors increase their risk of homelessness.

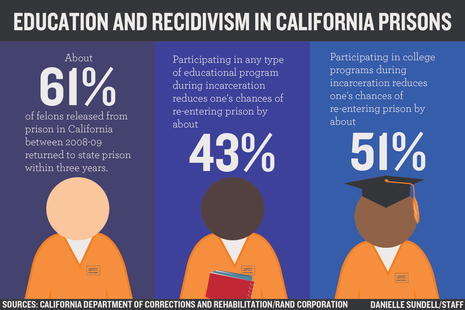

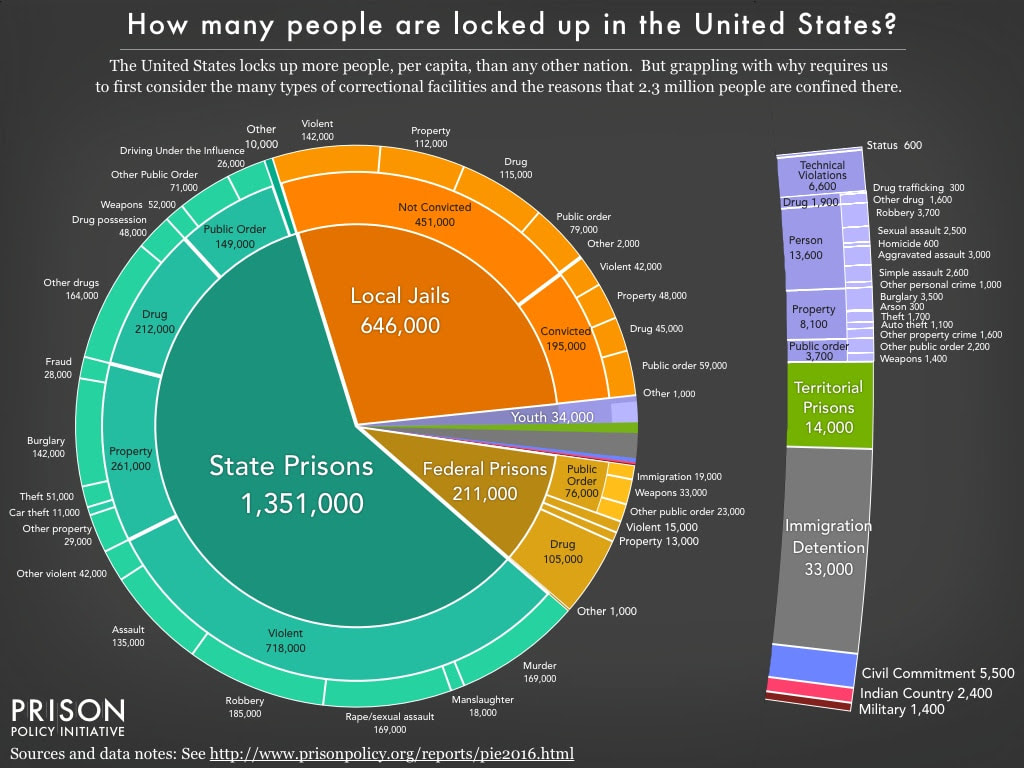

Preliminary evidence shows that pre-incarceration shelter use is the strongest predictor of shelter use following incarceration—a finding that may have implications for the targeting of services.[1] Without assistance, in particular with housing and/or employment, ex-offenders may find themselves experiencing homelessness or back behind bars. Evaluations in two states, Maryland and California, indicate low rates of recidivism and homelessness among former prisoners and inmates who received housing assistance, case management, and supportive services through state-sponsored programs upon reentry.[2] However, further research is needed to better understand services needs and the effectiveness of interventions among ex-offenders. Dana Hunt, an expert who has spent many years studying the criminal justice system, illegal drug use, and drug treatment programs, is working on an up-to-date synthesis of the evidence on criminal justice reentry and homelessness that will be available on this website soon. -- [1] Metraux, Stephen and Dennis Culhane. Homeless shelter use and reincarceration following prison release. Criminology and Public Policy; 2004: 3(2), 139-160; Metraux, Stephen. Assessing the impact of the Gaudenzia FIR-St. Residential Treatment Program in the context of prison release and community outcomes for released state prisoners with mental illness in Philadelphia: A report to the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections. 2007. University of the Sciences in Philadelphia. [2] Metraux, Stephen, Caterina Roman, and Richard Cho. “Incarceration and homelessness.” in Deborah Dennis, Gretchen Locke, and Jill Khadduri, eds., Toward Understanding Homelessness: The 2007 National Symposium on Homelessness Research. 2007 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Mass Incarceration Source: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2016.html Source: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2016.html

While this pie chart provides a comprehensive snapshot of our correctional system, the graphic does not capture the enormous churn in and out of our correctional facilities and the far larger universe of people whose lives are affected by the criminal justice system. Every year, 636,000 people walk out of prison gates, but people go to jail over 11 million times each year. Jail churn is particularly high because most people in jails have not been convicted. Some have just been arrested and will make bail in the next few hours or days, and others are too poor to make bail and must remain behind bars until their trial. Only a small number (195,000) have been convicted, generally serving misdemeanors sentences under a year.

|